Chapter Three: Learning to Play

To say that I was woefully unprepared for life after high school would be guilty of the gravest understatement. Looking back, I’d been horrendously cossetted against the Shakespearean arrows by protective parents, then by the closed environment of an exclusive boys’ boarding school. And I’d rebelled strongly and constantly against that protection, always being self-centered and cocksure of my ability to get through life in my own way and under my own terms.

That attitude would come to a screeching halt in 1972, when I was arrested and put on trial for my opposition to apartheid – opposition that was based on nothing but peer approval, really, because at age 17 (yes, I turned 18 long after my final first-year exams at Wits) I knew sweet F.A. about apartheid other than it was Bad, man. And my 100% academic failure – yup, four out of four courses – was like a bucket of cold water dropped on my head.

Year Two at Wits, so to speak, wasn’t any better. I lazed my way through the year, playing bridge in the student cafeteria instead of attending lectures, and all the time listening to the music (Cat Stevens, Jefferson Airplane, T. Rex, you name that early 70s music, they played it) that came through the tinny speakers of Wits Radio (not really radio, because it was piped, not broadcast).

Rock music had formed the background to my life in College, too, because it was the time of the Beatles, the Moody Blues, the Hollies, Traffic, the Doors, Cream and In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida, baby. But I’d listened to all this stuff purely as an audience, not knowing how it was constructed.

Which, come to think of it, was strange. When listening to classical music, of course, I could pick apart all the different instruments, identifying the different tones and modalities of clarinet vs. bassoon vs. French horn vs. the cor Anglais, violins vs. violas vs. cello, and so on – what is known academically as “close listening”. I’d had all the training in the world for that, thanks to Messrs. Barsby and Gordon’s Musical Appreciation courses and of course the choir.

But I’d never done it with modern music. Oh sure, I could get moved by a lead solo from Eric Clapton or Jimi Hendrix, and of course I could sing any part of a Crosby, Stills & Nash harmony and rejoice in the artistry. But really, I was just a spectator to the game instead of a participant.

So when I arrived in Margate (having freshly failed yet another year’s studies), I was secure in the knowledge that I’d mastered all three dozen-odd songs Mike Du Preez had given me. I expected that the next four weeks were going to be a breeze: play in the band at night, lie by the pool by day, and get paid for it. Living the dream, baby.

Except that I didn’t know how to play the bass guitar. Oh sure, I could play the notes just fine; but what I didn’t know was that in modern music, the bassist is tied to the drummer – the two are jointly called the rhythm unit, after all – and most importantly, the bass guitar is tied to the drummer’s bass pedal. So it wasn’t just getting the notes right in whatever key we were playing; I soon learned that whenever that bass drum was struck, there’d better be a bass guitar note striking at the same time, or else the band’s sound was as flat as a pancake. And of course the number of times that happens depends on the key signature, or timing of the piece or even of the bar (because the tempo often changes during the song, as well as the key).

Of course, I only learned of this new thing after we’d arrived, set up our gear and launched into a little practice session. Also of course, that little practice session turned into an all-day practice session so that the Idiot Ignorant Bassist could learn the differences in beats between (deep breath) regular ballads (2/4, 3/4, 4/4, 6/8, 12/8), up-tempo (4/4), waltzes (3/4), (polka (2/4), all the Latin tempos (cha-cha, samba, rhumba, tango etc.) and of course which one to play for the various ballroom dances such as the foxtrot, quick-step, Charleston, West Coast Swing, Dixieland jazz… I think you get the picture. Worse still, a supposedly-simple song like When The Saints Go Marching In would start off in 2/4, shift to 4/4 for the solo and then revert to 2/4 for the rest of the song – unless the pianist/band leader decided that the song needed another solo, of course – in which case Our Newbie Bassist would get into a sweat trying to play catch-up with the bass pedal, and usually failing.

What a nightmare. And we had not yet played our first night in the dining room.

To my everlasting relief, the only guests in the dining room that first night were not there for the dancing, only the dining, so they were out of the room by 9pm. And so two members of the Mike Du Preez Trio used the remaining three hours trying to teach their Accidental Bassist how to play his instrument. Then the whole thing began again the next morning at 10am till 1pm, break for lunch till 2, then again practice until 5pm, break to get showered and dressed in uniform (red-and-white striped or white and black-striped shirts on alternate nights, black trousers and -dress shoes – my old school shoes for added humiliation, because I didn’t have anything else), dinner at 7.30pm and then back on stage at 8 for the next four hours of torture.

And the same thing happened the next day and night, and the next day and night, and the next… five days in all till midnight on Sunday, then practice again on Monday, but! we had Monday nights off! So Mike gave us the night off from practice, too, the first since our arrival.

By the end of the third night the Mike du Preez Trio’s members were heartily sick of each other – okay, the other two were just heartily sick of me – so at this point I guess that I should spend just a little time talking about them.

Mike du Preez was justly well-regarded on the gig circuit (except by me apparently), and his knowledge of 1930s, 40-s and 50s “standards” was I think unparalleled. And when I say “knowledge”, I mean he knew the music and the lyrics to all those songs (maybe about three hundred?) and could play them, faultlessly and without any sheet music on the piano, organ, guitar and (to my utter humiliation) bass guitar. He was endlessly patient with me, but not in a good-tempered manner. This meant that he’d yell at me whenever I made a mistake or forgot something we’d practiced earlier – which only happened about every half-minute or so – until my nerves ran ragged. On one such occasion he must have seen that I was about to chuck it all in and leave, which made him even angrier. “You cannot fucking quit, sonny-boy!” he raged. “You’re supposed to be a professional musician and by God you’re going to act like one even if you’re nowhere close to being one!” Pause. “Now let’s do Desifinado again – yeah, I know we just did it yesterday, but you’ve probably forgotten everything about it.” (Which of course I had.)

A side note: I had discovered that if I stuck to playing the bass guitar softly with the treble turned almost completely off at both the guitar and the amp, the sound was quite muddy and indistinct: a bass tone but not necessarily noticeable as being out of tune. It was a trick I was to use many, many times in the future.

In my perpetual state of confusion, the only way I could even remember what key the songs were in was by watching Mike’s left-hand pinkie on the piano. If that finger played E-flat for the song’s opening, the key most likely was E-flat, and any key changes would be indicated by his playing a different note outside the E-flat scale. So I had to keep looking at Mike’s left hand on the keyboard and hinting for that note’s place on the fretboard while simultaneously trying to watch the drummer’s bass pedal to tell me when to play (a wrong note, usually).

The drummer was an old pal of Mike’s, Dick by name and a dick by nature. Outwardly a jovial sort, he was in fact mean-spirited and cruel, not just to me but to everyone, and with my residual private-school good manners, I was often appalled by his blatant rudeness. While Mike had his own room in the hotel, the hotel management had (in a moment of what I can only call cosmic bloody-mindedness) booked a tiny one-bedroom cottage up the road for Dick and me to share: him in the bedroom and me on a small uncomfortable cot in the living room. (Oh how nice, but as I’d slept on a horsehair mattress for two years in the Prep, this didn’t bother me too much.) So it was bad enough that I had to put up with his cutting remarks during the day’s practice and evening performances: I had to endure them in the lousy cottage as well, sleep being the only refuge. Apparently, Dick had a parallel career as a stand-up comedian, but I’d never heard of him. I learned that he specialized in a broad, Jerry-Lewis type of comedy, which I’d always hated anyway, and still do. (When I was a small boy, Lewis had once toured South Africa and my parents had taken me to see him in concert. Even as a child, I thought he was the unfunniest man I’d ever seen. So you can imagine my reaction to Dick’s description of his own act.) There were several times I wanted to punch him in the mouth, especially on one occasion when he said something unpardonably nasty about our employer, Rick the hotel manager.

I was to get on famously with Rick, a tall, slender dark-haired man in his, I guess, mid-thirties, a man who had (I was to discover) endless patience with his staff and a sense of humor to match. Having no one else to speak to, I bumped into him that Monday off in Reception, my ears still burning and my pride in tatters after yet another fearsome practice session. Clearly, he saw my distress, took me into his office, sat me down and started chatting with me, asking about my background and so on. He then told me the most appalling lie: he’d heard us practicing and was truly impressed by our dedication, and especially by my contribution (!) to the band’s sound. Apparently, after firing me at that first disastrous audition back in Johannesburg, Mike had called Rick and told him he would be doing the gig solo – but Rick wasn’t having any of it. “I booked a trio, not a pianist” he told me he’d said to Mike.

Which is why Mike had called me back for the gig, then.

Anyway, Rick said, “Why don’t you relax tonight? You’ve got the night off, so go down to the Grove and listen to the band, have some drinks and just sign for everything . I’ll tell the barman to comp you for the length of your stay here – but just for you, not for anyone else, okay?”

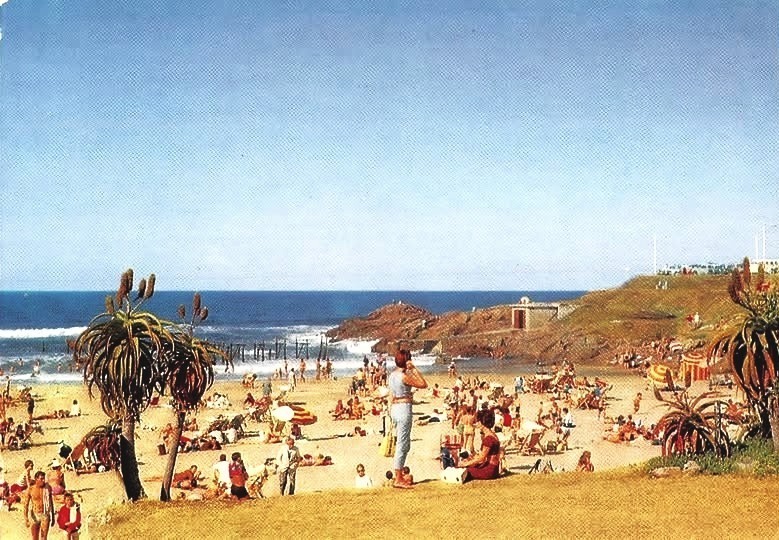

Margate was the largest of dozens of resort towns strung out along Natal Province’s South Coast, and was justly famous for its beach:

…which changed quite a bit during the holiday season.

The Margate Hotel’s Palm Grove Club deserves an entire book, let alone a few words in a work like this. Suffice it to say that it was probably the most famous of all the resort clubs on the Natal South Coast, having opened (I think) shortly after WWII, and just about every name band and orchestra in South Africa had played there at least once or twice. If you’d played the Grove, you’d pretty much made it.

I’d never heard of the place.

It was by then a vast, rather ugly structure (see below), but very much the place to go to when it was open – November through mid-January, and maybe over the June-July period, and only then.

(pics found SOTI)

So as instructed, I went down to the Grove, to be greeted by two young and very pregnant girls at the entrance. “The cover is one Rand,” the one said (about 25 cents in today’s US$, or the cost of a bottle of beer back then).

I didn’t have any money. I mean, I really Had. No. Money. I’d been surviving on hotel food and water since I’d got there, having used the last of my meager funds to pay for the gas needed for the four-hundred-mile trip down from Johannesburg. (I must have lost 10lbs in weight during that first week alone.)

So I shrugged miserably and turned away, when the other girl said, “Wait; aren’t you in the band in the hotel dining room? You are? Well then there’s no cover. Go on in.”

So I walked into the Grove that Monday night, and it was at that point that my life would irrevocably change.

– 0 –