…or Il Dolce Far Niente, as the Italians would have it — and why not? it’s about as Italian an attitude as one can get, where there’s an alternative to being busy.

I consider myself something of an expert on the activity, because for example nothing spells “vacation” better than lying on one’s back, emptying the mind of, well, everything and just looking at the sky. I can and have done that many times in my life, and only some vestigial Protestant work-ethic guilt keeps me at all busy.

But that’s not what I want to talk about today.

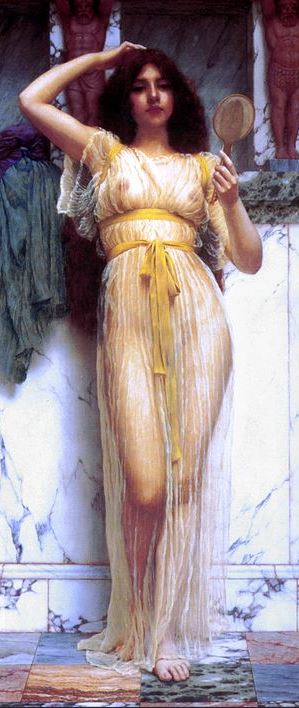

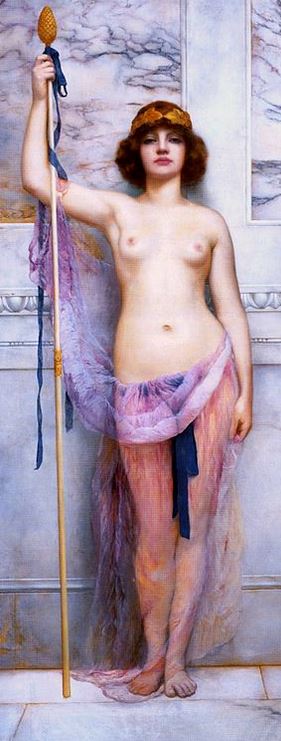

Instead, I want to point you to English artist John William Godward, who exemplifies to me the late-Victorian art movement that bypassed the strict Puritanism of the era, simply by virtue of the fact that one could show the naked or semi-naked female form without censure, provided that it was couched, so to speak, in some kind of Classical allegory. (“Venus In The Mirror”, for example, has been used as an artistic fig leaf for centuries.)

Well, Godward’s family didn’t much care for this attitude, and when he went to live in Italy with one of his models, they pretty much erased all memory of him out of their lives (literally; they cut him out of all family photographs; and as such, there are apparently no photos of him in existence). Anyway, they wanted him gone out of their lives, and he granted their wish by committing suicide at age 61.

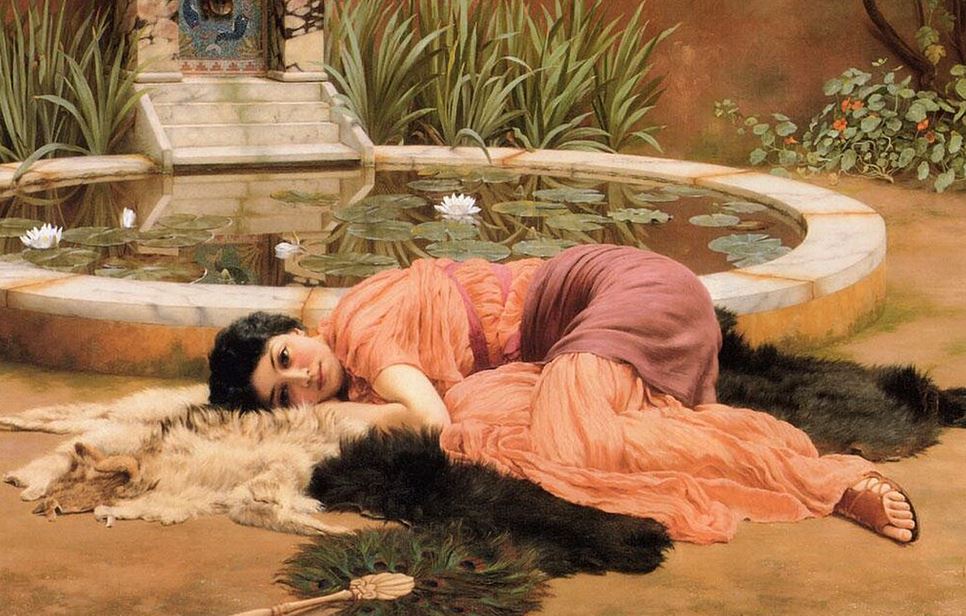

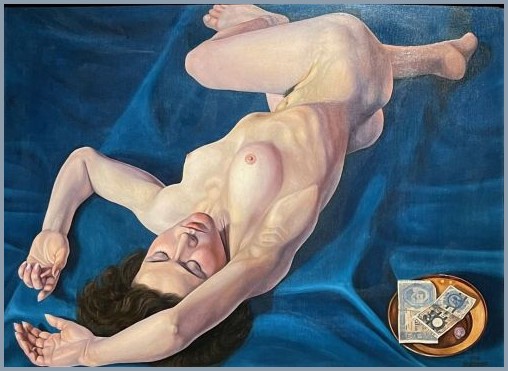

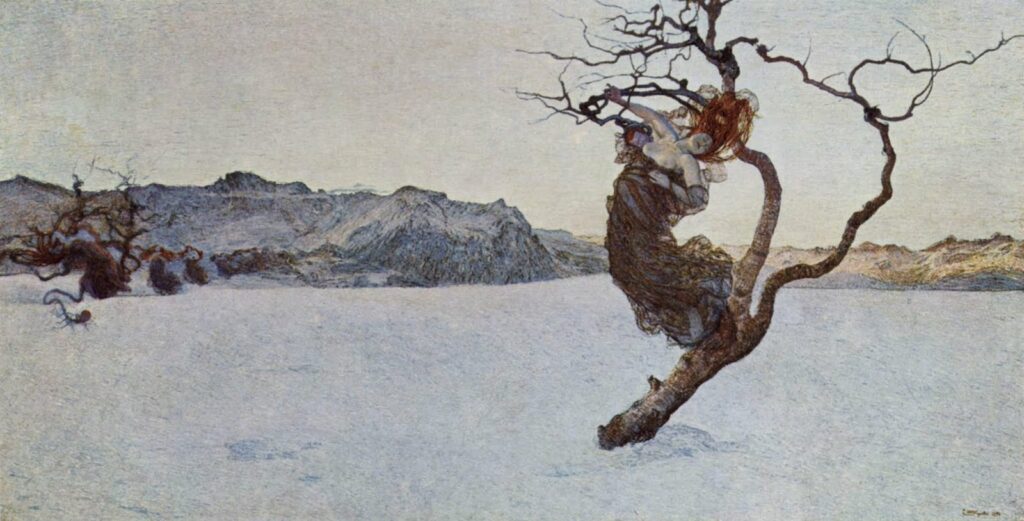

Godward is famous for his painting entitled Il Dolce Far Niente, and in fact used it as a theme for a great many of his later works. Here’s the first:

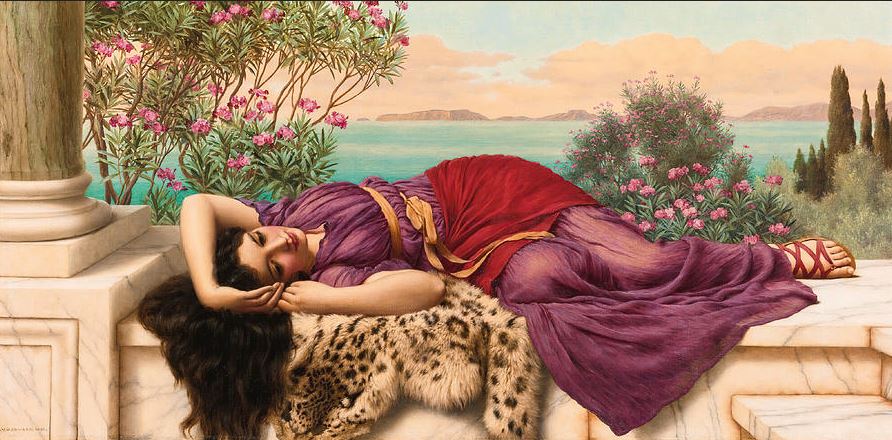

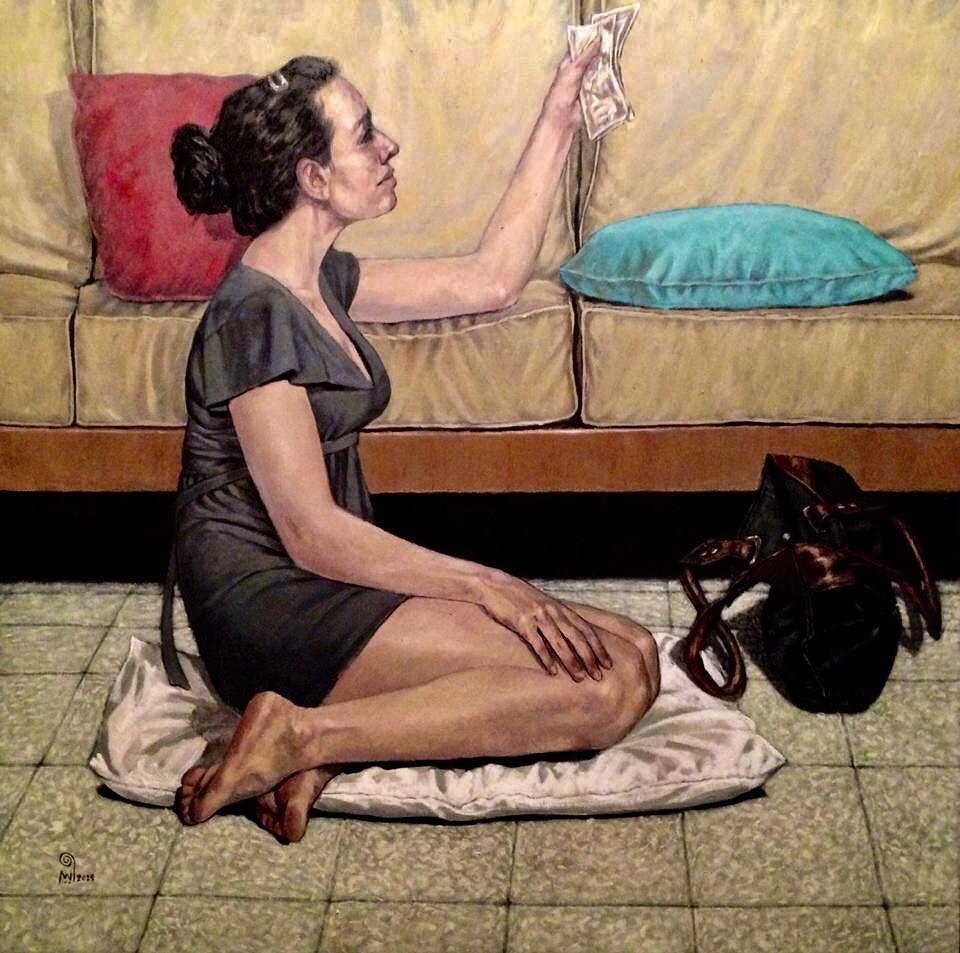

And a few other examples in the same vein:

I love that he captures the feeling of dreamy indolence of a summer’s day in Italy — note the classical clothing and setting of each — along with a subtle underplay of eroticism. (In turn-of-the-century Britain, by the way, there would have been nothing at all “subtle” about it, hence the scandal.)

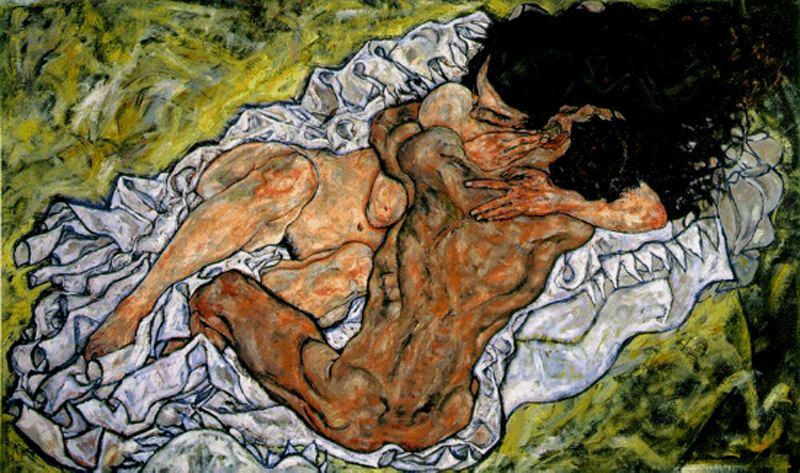

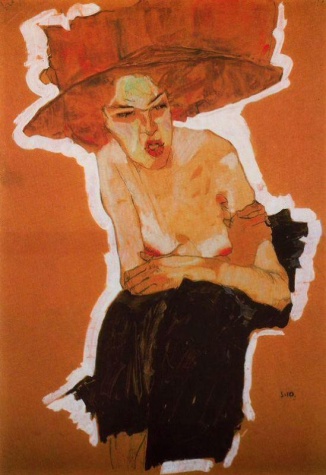

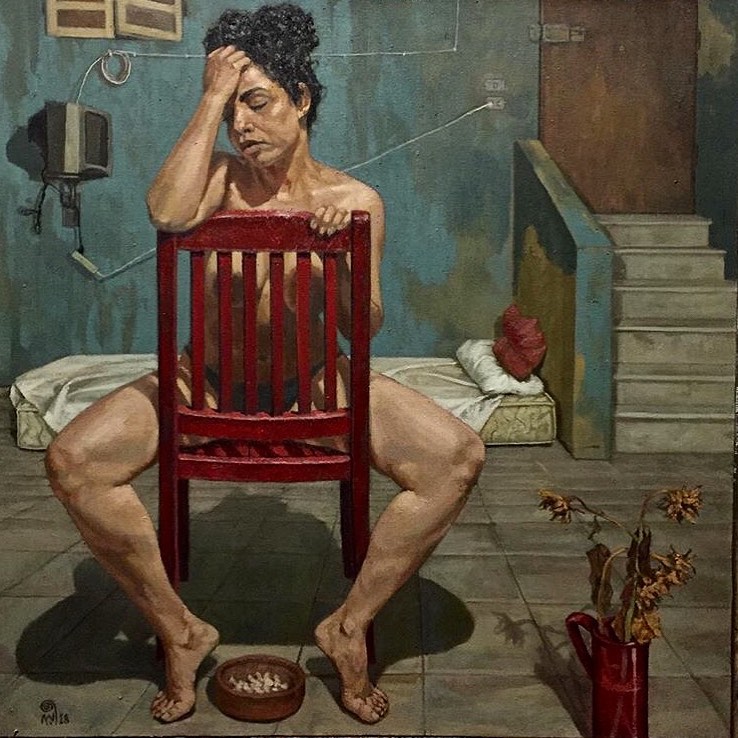

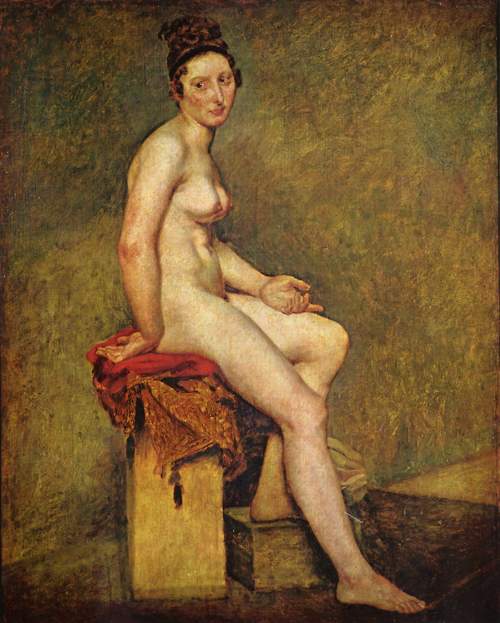

Of course, he didn’t stop there. Still in that disguise of Classicism, here are a couple more daring visions:

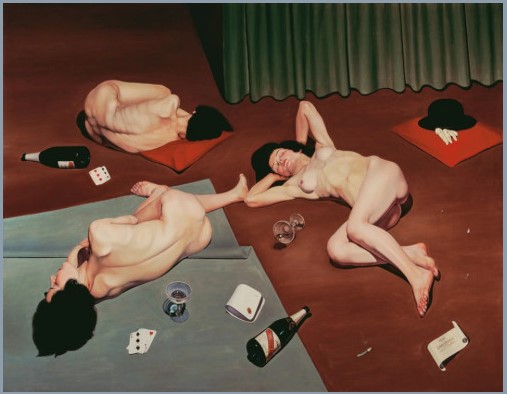

And of course, there were those works which threw away all pretense at Classicism (and clothing too):

To modern eyes, Godward’s style might seem stilted and unrealistic, perhaps. But at the time he painted them, that’s about as “modern” as they got.

I like just about every work he ever created.

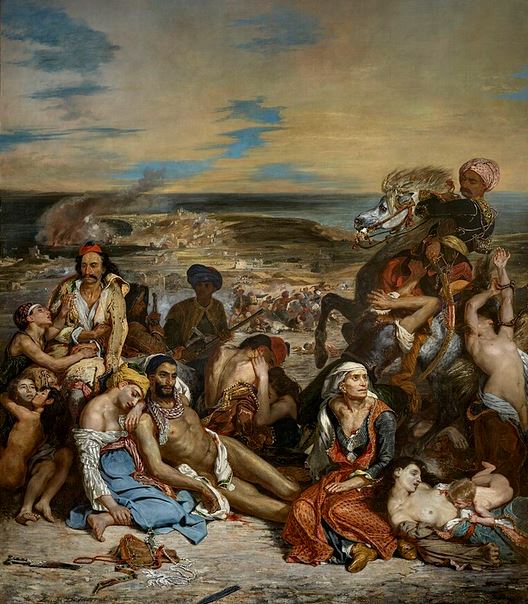

Death of Sardanapelus

Death of Sardanapelus