(Previous: Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5)

Chapter 6: Building Pussyfoot

Along the way, we’d decided on a name for the band: Pussyfoot Show Band, which was a triumph of 70s attitude over sound marketing principles. I have to admit that I don’t remember who came up with the name, but I do remember being its most ardent supporter. Knob was the first to voice an objection: “Who in their right mind,” he asked, “is going to book a band with a dirty-sounding name?” (Not many, as we were to find out.) Still, there we were.

Of course, we also didn’t have a “show” of any description, unless you counted the bassist leaping all over the stage like some demented animal while the other front three stood like statues, intent on getting their parts right.

And speaking of parts: one of the benefits of having Mr. Filthy Perfectionist in the band was that we were — considering we were a band who’d only been playing together for a few months — a tight sound, and quite well-rehearsed. It helped the others overcome their stage fright somewhat; I, on the other hand, was brimming with confidence — confidence being that feeling you have before you know any better, of course.

Anyway, we arrived at Rob’s (and Cliff’s) old high school a full hour and a half before we were due to start Because Kim Insisted We Did. (I had, and never lost, a dread of us arriving at a gig only to find out that we’d left something behind, or a car carrying gear broke down en route, or some piece of equipment didn’t work: I feared all the many things that would prevent us from starting at the time we’d agreed. And in my mind, not starting on time was the infallible mark of an unprofessional band, so we would always arrive very early for a gig, even years later when we’d got the off-loading / setup thing down to a fine art and could do it all within half an hour.)

So right at 10am, the MC of the show (who looked about nine years old) opened the proceedings with a couple of announcements, then handed the thing over to Pussyfoot. There was a massive crowd, nearly three hundred kids (with a lot more to come) and the auditorium was jam-packed.

We would go on to play countless gigs after that one; but nothing ever topped this high school party, for all sort of reasons. For starters, we could play anything, any song at all, even the ones we’d written off as unsuitable gig material, and whatever we played, the kids danced their asses off. A couple of honorable mentions: Golden Earring’s Radar Love (which had taken us ages to learn, not because the music was difficult, but because all the tempo changes and different phrases were complex, confusing and difficult to remember in sequence), Santana’s Soul Sacrifice — the Woodstock version, sans Hammond organ(!), but complete with drum solo from Rob — and of course songs like the Doobie Brothers’ Long Train Running and Listen To The Music, Fleetwood Mac’s Albatross and Man Of The World, and Sweet’s Fox On The Run (which nearly caused a riot, and which we performed exactly like the original, complete with castrati harmonies).

Of course, you can have too much of a good thing, and we soon learned why. After the third hour, my fingertips were so painful that every note was torture: I half-expected to see blood running out from under my fingernails. Donat and Kevin were likewise stricken, because we had not prepared for this kind of thing and we were, to put it mildly, taken aback by the strain of prolonged playing (fifty minutes on, ten minutes off, according to the rules of the dance marathon).

And here, the aforementioned Soul Sacrifice deserves a line or two. We’d learned it so that we could feature Rob’s fine drumming, even though drum solos, in a gig context, are generally death to any dance floor activity. However, on this occasion, I figured that the kids wouldn’t mind too much, so I called the song (to the utter consternation of the others), and off we went. However, the version we played that day was a little different from Woodstock in that during the drum solo, I motioned Ken and Donat off the stage and setting down our guitars we went off for a pee break, leaving Knob and Cliff on stage (the latter beating the hell out of a pair of congas) for what seemed like ages. Then we finally sauntered back on stage, picked up our guitars and at the appropriate time launched into the finale of the song. Fortunately, its extended length ran right up to the fifty-minute mark, so we took a break.

I had never seen the normally-cool, unflappable Knob sweat like that. Nor had I ever heard him cuss us out so profusely.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing, of course. Cliff’s voice gave out completely early during the third hour, which meant that the three of us had to carry the vocal load together for the rest of the performance. This was not something we’d rehearsed, and it put a level of mental strain onto us that persisted for years, and not to our benefit either, as you will see later. For my part, I was absolutely furious at Cliff, as much for his attitude as for his failure at his only job. He seemed to just shrug it off with a “What can I do about it?” expression. Not for the first (or last) time, I wanted to punch him in the face. But the band couldn’t quit; that would have been the height of unprofessionalism, so we soldiered on. From that day on, however, Cliff’s days in the band were numbered, although I was the only one who knew it at the time.

The final hour of the gig saw five exhausted musicians pretty much going through the motions — we were more tired than the dancers — and indeed the last set list was just a rerun of all the songs I’d judged had been the biggest crowd-pleasers so far. Anyway, we played the last song, whereupon the 9-year-old MC bounded back on stage and said simply, “We’d like to thank Pussyfoot — ” and his voice disappeared into an earsplitting storm of screams from the three hundred-odd girls in the audience. Good grief, it sounded like the Beatles had just finished a concert. On and on it went, and when I glanced over at the other guys I saw just the same reaction from all of them: astonishment, and embarrassment. Kevin was blushing so deeply that his skin was the same color as his hair, and Donat was looking at the ground, shuffling his feet. Even Knob just sat behind his drums, his mouth open.

So that’s what it was like to be rock stars.

After the excitement of that gig we took a week off from practice, as much out of exhaustion as to give our aching fingers a chance to recover. (Knob, by the way, hadn’t escaped unscathed: he had four massive blisters on his fingers courtesy of his drumsticks.)

But when we did finally get back together, we were faced with an inescapable fact: we needed a keyboards player. But we had no clue where to get one.

Here’s what had happened. The guys in the band had become friends (well, except for me and Cliff), and without ever talking about it, I think we shrank subconsciously from inviting a stranger to share our little partnership in case it didn’t work out. From my time with the Trio in Margate, I knew what it was like when nobody in the band liked the others, and I’d shared that with the guys much earlier on. It was all very frustrating; but in the end it was Cliff (!) who came to the rescue. Apparently, he had a buddy who’d just finished his draft commitment in the Army, and said buddy knew a guy in his unit who was a keyboards player. So the phone lines hummed, and at our very next practice came Mike (“Pussfaze”, a play on his surname), complete with a massive Hammond organ and Leslie speaker.

Mike was a very short, wiry guy with, we were to discover, a sharp and incisive sense of humor and a no-nonsense way of looking at the world that was something quite different from the rest of us dreamers. While not the most creative of keyboards players, he was absolutely rock solid when it came to playing what we’d rehearsed, and in fact I do not recall a single occasion, ever, when he made a mistake during a gig — I mean, he never once played a dud note over the next decade or so that we played together. And he was a brilliant organist: there was not a single organ part, from Deep Purple’s John Lord to Uriah Heep’s Ken Hensley to Santana’s Greg Rolie that Mike couldn’t play, note-perfect. In that regard, he was a monster.

Way back, I’d learned to play Booker T’s Time Is Tight, and so on this day, without any preamble, I launched into the bass intro. To my delighted astonishment, Mike just started playing the organ part, perfectly, and Rob, who’d not been expecting anything like this, picked up the drum part. Then we stopped to let Kevin figure out the lead solo — he knew the song, but he’d just never played it before — and of course within a few minutes he had it down pat. So we played the whole song from beginning to end, then played it again, and it too became a permanent part of our repertoire.

There were a couple of songs I remembered from the Margate gig, and wonderfully, Mike knew them too. So Gershwin’s Summertime and Nat King Cole’s Fascination came up and were dealt with, with almost contemptuous ease.

We knew after that very first practice that Mike was going to be a keeper, and even though I got some astonished looks from the others, at the end of the practice I said, “So Mike… do you wanna join us?” He thought for a moment, then nodded. And that was that. We had a keyboards player.

Which led us to the next issue. Up until now, we’d been able to carry all the band’s gear in each of our cars (Knob borrowed his mother’s Passat station wagon to carry his drum kit because his own car was a Daimler 250 2-seater). But with Mike’s Hammond and Leslie speaker… he’d borrowed a small truck to get his gear over to my house for this first practice, but he wouldn’t be able to do that in the future.

Clearly, we were going to need a van… but how could we afford one? Well, we couldn’t; but fortunately, there would be a couple of months before we would get our next gig. Then I saw the answer to our dreams. Brazil had started making cheap copies of the early-1950s VW panel vans, and VW South Africa saw the success of that business and started importing them, and selling them at a ridiculously low price. It didn’t matter because none of us could afford the deposit, and as students / low-paid workers, none of us had a credit rating that would enable us to finance the thing.

My father had been listening to us play — he could hardly have not heard us without leaving the house and going far away — so one night I was talking to him about our troubles with the gear when he said, “You boys have been working really hard, and it’s a shame that you might not be able to get around to play at parties and such. So here’s what I’ll do: I’ll take care of the deposit for you, if you’ll handle the monthly payments. And after it’s paid off, you can just continue the payments until the deposit is repaid.”

Thus: Fred joined the band.

(not the actual Fred, but the color is correct and yes, there were swing-open back doors, sliding windows and a split windscreen)

(not the actual Fred, but the color is correct and yes, there were swing-open back doors, sliding windows and a split windscreen)

I think that it was at this time that both Donat and Kevin decided to get bigger amps, and no doubt spoiled by Fred’s capacious interior, they got the same amp: the huge Fender Dual Showman stack, which stood almost head-high and contained four giant 15″ speakers:

I too had splurged, and got a Fender Bassman 100 stack, which was almost as big, containing as it did four 12″ speakers in its cab:

Now we could play loud, baby. And we did.

But the greatest change came when Kevin and Don started complaining about my bass sound — not sharply, but like after practice when we were having our customary hamburger at the local steakhouse, one or the other would sigh and say things like “I just wish your bass sound was more… punchy.” Then one day I got sick of it all, and said, “Okay, what bass, exactly, do you think would make my sound better? I already have the right amp.” There was a long pause, then from Donat: “The Rickenbacker, like Chris Squire plays.” I thought about it for a moment, then said, “Okay; I’ll see if I can get one. Just don’t expect me to play as well as Chris Squire.”

When I went into Bothners and asked Eds Boyle about a Rickenbacker, he just grinned. “You’re not going to believe it, Kims… one just came in. I haven’t even taken it out of its packing case yet.”

And thus did I get — at huge expense that I couldn’t really afford — my next (and last) bass guitar:

(Okay, Kim, you may ask: how expensive was it? answer: it cost

only a couple hundred dollars less than Fred.)

But the change the Rick brought to the band’s sound was immediate and life-changing. Finally, we were starting to get our own unique sound.

With all that taken care of, we started to expand our repertoire, big time, and were no longer constrained by the lack of a keyboard player. First came Santana, and most of the songs off his Abraxus album — a permanent fixture was the exquisite Samba Pa Ti — and then we taught Mike Soul Sacrifice — minus the extended drum solo — and to our amazement, he nailed the organ part after only a few repeats. So we could finally play Soul Sacrifice in the manner it deserved.

But without any gigs on the horizon, we concentrated on playing music that would extend us as musicians, and so along came songs like Camel’s Six Ate and Uriah Heep’s July Morning. (We were never to play the latter at any gig because it was just not a “gig” song: too many stops and starts, too many tempo changes — but that never stopped us from learning it, or playing it for months thereafter.)

Side note: I don’t think that people nowadays can tell how difficult it was to gather material back then. There was no YouTube, no Spotify, no kind of streaming music whatsoever. Basically, what we (and I think other bands) used to do was either buy the 7″ single record or tape the song off the radio, if you could get to it in time, and then we’d pass the tape or record around the band for each member to learn their specific parts: a long and time-consuming effort. (Remember too that back then, even cassette tapes were A New Thing — my old Fiat had had an 8-track cassette installed, for example.)

Paradoxically, I quietly started to steer the band towards gig songs that wouldn’t tax Cliff’s voice: stuff like Hedgehoppers Anonymous’s Hey and Stevie Wonder’s Isn’t She Lovely (suitably lowered in key, of course).

Still: no gigs.

One day I was in Bothners — trying hard not to spend any more money that I didn’t have — and when I complained to Eds about the no-gig thing, he looked shocked. “Have you spoken to an agent yet? No? Why the hell not?” and he produced a card with “Morris Fresco (The Don King Organization)” printed on it.

So the telephone wires hummed, and we arranged for Morris to come and listen to us. For the occasion, as my parents had taken off for a long weekend’s vacation, we cleared out the living room and set up on the one side, playing towards the couch we’d left at the other for Morris to sit on. And when he arrived, we launched into what we thought was a good sample of our repertoire.

And we blew it.

Not because of our playing, mind you: everything we played, we played flawlessly despite our considerable nervousness. But instead of playing the kind of songs that would get us gigs — the dance tunes, the pop songs, the ones people would recognize, we were too good for that, oh yes we were — we played all the heavy stuff, the complex songs because, you see, we wanted to impress this Great Big Important Agent and dazzle him with our musical ability.

Had we been auditioning for a club gig, mind you, this might have been a decent approach. But none of the stuff we played would have worked at a wedding reception, or office party, or any kind of mainstream occasion.

So at the end of it all, Morris complimented us on our sound and our ability, and took his leave, saying he’d be in touch.

I don’t think we ever got a single gig from the Don King Organization.

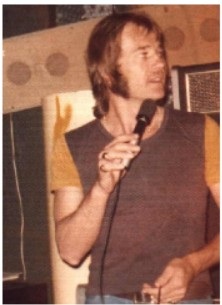

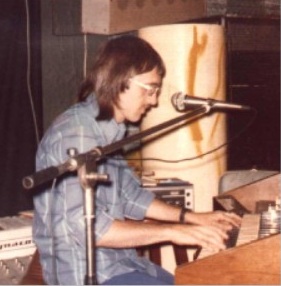

But we didn’t know that at the time, of course, so we carried on rehearsing. And now I think it’s time for everyone to see this Pussyfoot Show Band:

(from top left, clockwise: Cliff, Knob, Donat, Kevin,

Mike and Kim)

Yeah, we didn’t look much like a rock band, but at least we sounded like one. And our next gig was not at some party or other: it was a residency, in a restaurant.

– 0 –