Stop the presses! Here’s the latest kitchen fad:

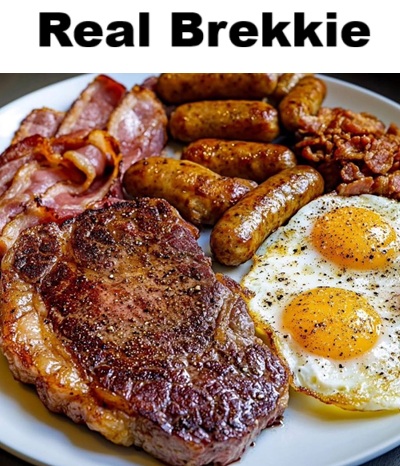

Serious home cooks looking to create a restaurant-style kitchen in their own homes are lusting after yet another piece of culinary kit.

Surfaces may already be groaning under the weight of appliances such as air fryers, espresso machines and top-of-the-range mixers – and let’s not forget the pizza oven in the shed, but middle-class foodies are now adding deli-style meat slicers to their polished countertops.

The ‘industry’ style equipment, which ranges in price from around £50 for a budget version on Amazon to the early thousands for an all-singing, all-dancing one, can precision slice through everything from smoked salmon to hams and cheeses – and even sourdough – with ease.

And while they may seem like an indulgent addition to an everyday kitchen, top chefs say they’re worth the investment – because not only will your charcuterie taste superior, but you can also buy it in bulk, which almost always saves money.

There’s less waste too, because you slice what you need, ensuring wafer-thin sheets of Parma ham don’t go unloved in the fridge.

The slicers – both hand-operated and electric – work by cutting food to uniform sheets, as thick or as thin as you’d like, which can affect flavors significantly, say those in the know.

Well, yes. The above article appeared in the Daily Mail yesterday (February 12, 2026).

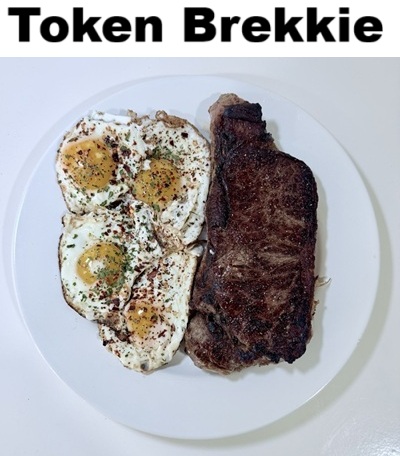

Then there’s this:

…which appeared in this post, dated Nov 25, 2023.

Good grief; for once, I’m actually ahead of a trend.

No need to thank me; it’s all part of the service. (Oh, and don’t let the product description fool you. I used the above machine to slice meats like salami, ham and beef for years.)