Chapter Two: Getting The Gig

At the age of sixteen, long after the age when most people start playing a musical instrument, I decided to learn how to play guitar.

I don’t honestly know why I decided this; perhaps I’d been at a party or picnic when someone played a guitar, or maybe it was hanging out with Gibby, who played both piano and guitar, I don’t recall. I’d had piano lessons for two years in the Prep, which had helped my musical theory proficiency, but I’d been put off by the drudgery of practice necessary to become keyboard-proficient – a dislike that was to curse me for the rest of my musical life – and plugging away at the ascending- and descending scales became absolute torture. When I got to the College, I told my parents that I wasn’t going to continue piano lessons, to their great disappointment.

But guitar was a different story. My fumbling and painful learning on the fretboard became less of a chore, because unlike scales, the mastery of chords meant the ability to actually play a tune. To his everlasting credit, Gibby lent me his guitar, a battered old Hofner nylon-stringed thing, and it was on this that I tortured my dormitory companions for the next year or so, painstakingly trying to place my fingers on the fretboard as demonstrated in the “Teach Yourself Guitar” pages of chord charts that were published in some magazine or other each week. As I recall, the very first song I learned was Creedence Clearwater’s Bad Moon Rising, followed soon thereafter by Proud Mary, and then more and more followed as I got a little (but not much) better; although I was able to play bar chords after only a couple months and, it should be said, some coaching from Gibby.

One of the guys in my Physics class (Richard Hammond-Tooke) had a book of songs with not only the chords but the lyrics handwritten therein, and he lent it to me to copy. To my horror, some of the songs (e.g. Blood Sweat & Tears’s Spinning Wheel) used chords that I hadn’t seen anywhere on the rudimentary chord charts (E-flat minor 7th, WTF?), which set off a mad scramble to find them printed somewhere. Even worse was when I tried to use actual published sheet music; while I could of course read the musical notation with as much ease as reading English (thank you Messrs. Barsby and Gordon!), translating each note into its position on the guitar’s fretboard was another thing altogether; but I persevered because I wanted to become a guitar player, damn it.

What amazed me was that in the course of learning all the fifty-odd songs in Hammond-Tooke’s songbook, I’d learned to play the Beatles’ mournful ballad Eleanor Rigby. Well, of course I wasn’t going to play that syrupy nonsense, so I turned it into a bluesy/jazzy arrangement instead, complete with rasping vocals <i>à la</i> David Clayton-Thomas of BS&T. When I played it to Richard, he listened in stunned silence, and at the end blurted out, “You should do this professionally!”

On such small seeds do plants often grow.

Next came GROBS. GROBS was a show that the pre-Matric (11th grade) class would put on each year, with comedy skits, musical numbers, magic tricks, poetry reading and other such stuff on the playlist. What set it aside from all the other activities was that is was put together solely by the boys, and not by the teachers. It was performed only for the school – the teachers were not going to let us loose on the public, and especially on parents – and it would take place on a Saturday night in the school hall. (Remember, we were mostly boarders at St. John’s, so a weekend night in school was no big deal.)

In great excitement, Gibby and I decided to form a band to play a couple of songs, me on guitar and he on bass. Of course, I didn’t have an electric guitar or amplifier, and while he had a Hofner “Beatle” bass, he likewise had no amplifier, but cobbled together something from the school’s stage PA system. Then we got a couple of other guys: Hamish Brebnor had a set of drums, and Paul Garwood had an acoustic guitar. So bass, two guitars and drums – if it was good enough for the Beatles, right? We rehearsed for a week or two beforehand, and then Garwood pulled out for no reason, two days before the show.

Panic!

Fortunately, two other guys stepped forward: Chris Chomse and Alistair Louw, both of whom had electric guitars and amps, offered to join. Both were already members of bands – garage bands, but hey – and they would bring not only their experience but equipment! to the gig. Problem solved.

However, whatever songs we’d originally planned to play were tossed out as being stupid, and we ended up playing The Who’s version of Summertime Blues (with me on solo vocals, doing my best Roger Daltrey impersonation) and the Rolling Stones’ Paint it Black, Alistair doing his impersonation of Mick Jagger. So I had to play lead guitar in the latter song, and here was my first lesson in rock music: I was okay playing chords on guitar, but lead guitar? Total shit.

Nevertheless, the show had to go on, so I sweated it out, practicing as much as I could before the fateful night. It didn’t help that my after-school hours activities were consumed by hockey practices and a couple of matches against other schools as well as choir practice, but came the night, came the player and I fumbled my way through the Stones classic with nary a misplayed note. (I didn’t, and still don’t know the lyrics for Summertime Blues but I just sang any old thing in an incomprehensible fake Wolverhampton accent – something I would do again and again for the next fifteen years.)

To my astonishment, the gig was a complete success: instead of being insulted and cat-called, our set was met with loud and sustained applause. The only negative came when we were called out for an encore, and had to refuse because we only knew two songs. Much booing and whistling followed.

Lesson: always have more songs to play than the occasion demands.

But that loud applause was another little seed.

I should point out that my childhood shyness had almost completely disappeared by this stage in my life, for two reasons. Firstly, I’d grown up physically and thanks to the compulsory sport regime, I was of fairly impressive stature. Secondly, adolescence had hit me, and along with only a minor brush with teenage acne had also come a rather impressive way with the girls. (I’m fairly sure that a series of casual girlfriends, plus my loss of virginity at only a couple weeks after my sixteenth birthday were largely responsible.)

My nickname was “Poke”, bestowed upon me by my girlfriend of the time and quickly picked up by my leering circle of friends, the bastards. Even my housemaster referred to this flaw in my character as “toujours chercher la femme”, which says it all. (I was faintly surprised that the old bastard didn’t say it in Latin.)

But back to the music. I left high school and started my first year at university, which ended up being a total failure. From a star student at St. John’s (a First, along with a couple other academic accolades), I turned into a total failure, because nobody had thought to warn me that the amount of work required for a First at high school was the equivalent of half the amount of study required per course at university. So my first year at the University of the Witwatersrand was a complete disaster. (It hadn’t helped that almost an entire semester was spent in court, having been arrested for participating in an anti-apartheid demonstration on campus. But to be honest, the writing had been on the wall ever since the half-year exams, which I’d likewise failed, unanimously.)

Musically, however, it was another story. I’d enrolled in the Wits Dramatic Society and performed in the chorus of Oklahoma!, but it really bugged me that the months and months of rehearsals had ended up with only a week’s worth of performances.

Then in the second year after high school matriculation, I was invited to join the PG Players, an amateur musical group from the Johannesburg suburb of Edenvale. The invitation came from my old school friend and choir-mate Mark Pennels, who’d met Peter Griffiths (the “PG”) and recommended me to him. I didn’t really want to do it, but Mark prevailed on me with the plea that they were desperately short of men who could actually sing. So I joined the group and set about rehearsing for the performance of Ralph Trewhela’s El Dorado, a story set in Gold Rush Johannesburg of the late 1890s. This time, though, I wasn’t in the chorus but part of a comedy duo, playing the part of a hobo, and singing a duet with Danny O’Connor.

The leading man was a tenor named Mike du Preez, who (I later discovered) was actually a well-known pianist and band leader who’d appeared on TV shows and was much in demand on the cocktail- and cabaret circuit.

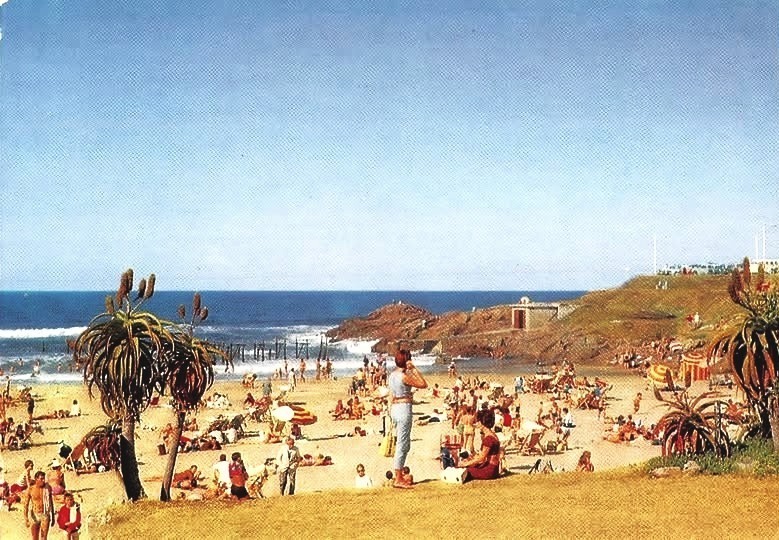

Towards the end of the show’s run, Mike came up to me and said, “Mark Pennels tells me you can play bass guitar. Well, I need a bassist for a Christmas gig I’ve got in Margate” – a seaside town on the South Coast of Natal – “…so are you interested?”

Now I need to be clear on this point. Gibby had gone off to do his military service (ending up as an armored-car driver), and had asked me to “look after” his bass guitar – that old Beatle violin bass, and I used to sit and pick at it idly while reading a book; making a sound but not actually playing anything. Mark had seen me doing this during his several visits to my house, hence the recommendation to Mike.

Now I could have ‘fessed up and told the truth: that I was an absolute novice, nay worse than that, and had no idea what was involved.

But I didn’t. Instead, I said: “Sure. What dates are we talking about?”

So I’d landed my first proper gig, not in some garage band or anything like that. No; I was going to be playing professionally with a renowned band leader and (I learned) a very experienced drummer, in a trio. And anyone who knows about this stuff will tell you that a trio is one of the most difficult gigs to play, because there’s absolutely no place to hide. Each part has to perform perfectly, and all have to mesh together withal.

Worse still, I was completely unfamiliar with — and didn’t like — the material, which was to be largely jazz standards of the Cole Porter-Dick Rogers-Hoagy Carmichael-George Gershwin genre.

And I didn’t even have a bass amplifier.

Of course, Mike insisted on a quick rehearsal a week before we left for Margate, so I called on an old friend from university who knew about such things, and asked him if he could make me an amp in a week. As luck would have it, John actually had one lying around in his workshop so I bought it from him on trust, promising to pay it out of my salary from the gig. (I was lying in my teeth, of course, but times were tough and I figured I could always find a hundred bucks somewhere.)

Anyway, I arrived at Mike’s house like Louis XVII walking up the steps to the guillotine. The amp, however, was impressive: a “head” perched atop a truly massive speaker cabinet – four 12-inch speakers, even, so Mike must have thought I was a pro. How wrong he was.

Actually, it was even worse than I’d dreaded. There’s no place to hide in a trio, and there was even less place to hide when it was just the pianist and me. I couldn’t play a single song, not even the easiest of ditties. After about twenty minutes Mike threw up his hands and fired me on the spot. So I slunk off, tail between my legs, but with what I had to acknowledge was a profound sense of relief.

Then two days later Mike called me up. “Well, I can’t find another bassist at this short notice, so we’ll just have to make it work somehow.”

I gulped, and said “Thanks.” Then something clicked in my brain and I asked. “Do you perhaps have any sheet music for the stuff we’re going to play?”

“Not much, maybe thirty or so songs. Why?”

“Well, I might not be able to play the music, but I can read it,” and I told him how I’d taught myself to play guitar by doing just that, and of my choral background in the St. John’s College Choir.

There was a stunned silence on the line, and then Mike said, “Do you think you can learn thirty songs before we leave for Margate in four days’ time?”

“Absolutely.” (Once again, lying like a Clinton at a press conference.)

But in the end I did, simply by going without sleep for four days and playing, as the story goes, until I had blood coming out from under my fingernails. I had done some difficult things in my life so far, but nothing could compare to this.

How I made it the four hundred miles down to Margate without falling asleep at the wheel is a miracle for the ages.

And the next four weeks were to change my life.

– 0 –