Two Americas

Consider these two statements:

“In this country there are two Americas: one for the privileged who get everything they want, and one for everyone else who struggle for the things they need.” — Sen. John Edwards

Now this, earlier, statement:

“There are two Americas — and millions of the people already distinguish between them. One is the America of the imperialists — of the little clique of capitalists, landlords, and militarists who are threatening and terrifying the world. This is the America the people of the world hate and fear. There is the other America — the America of the workers and farmers and the ‘little people’.” — James P. Cannon, to the 1948 convention of the Socialist Workers Party.

At their foundation, both these statements have one thing in common: envy, the root of all socialism. Both speakers are “populists” (which, history has shown, pretty soon turns into socialism).

But they’re both wrong. America is not divided into the “haves” and the “have-nots” — at least, it’s not a static condition. Anyone in America with a work ethic, application and a little luck can make it big, from humble beginnings. Edwards himself is the proof thereof. But it’s not even that difficult to “make it” in America: almost anyone can get into the middle class with just a modicum of hard work — which is why the American standard of living is higher than that of any other nation in the world. The division between the classes is both flexible and permeable.

But America is divided into two. It’s just not divided along the lines that Edwards and Cannon stated.

Unfortunately, the schism is not economic, but philosophical — and I fear that this situation is not so malleable.

I used to think that the Red & Blue America map marked the demarcation, but it’s not that simple: the two Americas are not separated by their geography (although this may be a partial explanation of the phenomenon).

Perhaps it would help if we looked at the two philosophies which are struggling for dominance in America right now. This is not meant to be a definitive breakdown of party differences (there are plenty of people in each party who espouse at least elements of the “other” party’s principles), but let’s just go with that as a first step.

In fact, it would be better to ignore the parties’ platforms, and see at the end which party has the closer affinity to that set of principles. (Do not expect dispassionate analysis from me, by the way, because while I can identify the philosophies, I do find the one deeply repugnant.)

What are these two philosophies?

They are the individualists and the collectivists. The terms are pretty self-explanatory, but let me explore each in a little detail nevertheless.

The individualists recognize that the most effective actions are those taken by individuals, or by short-term voluntary groups of individuals, to address specific needs and concerns. (Where the needs are either long-term or constant, of course, that’s a different issue, which I’ll explore in a moment.)

Mowing the lawn, for example, is most efficiently done by each homeowner, rather than by the Council Lawnmowing Department.

Self-defense, of course, is far better left to the individual rather than depending on the State to fulfill that need — as the experience in Britain has most recently proved.

Individualists also feel that, in general, people can be trusted to do the right thing. Yes, to use but one example, some people (about half of one percent of a society’s population) will always resort to crime rather than work to improve their lot in life — and that constant 0.5% requires a standing police force to address the issue. But even then, the percentage of police officers to the total population need not be that great, if that’s all they’re charged with.

To the individualists, who generally trust others, the commission of a crime is not just an offense against society, it’s also a betrayal of the common trust — which is why, for instance, the individualists are in favor of a few laws, but that those few be sternly enforced.

Other short-term solutions involve “helping hands”: the notion that people suffering one of life’s temporary setbacks be helped for a while by the voluntary efforts of others.

Where there are constant and long-term issues, there is obviously need for a full-time solution which transcends the ability of a group of individuals to address. The Founding Fathers’ fear of a standing army notwithstanding, it’s obvious to all but the blindest ideologue that the defense of the nation is a collective issue best addressed through a permanent institution. (And the Founding Fathers had no problem with a standing navy for that precise reason.)

The concept of individualism, it should be noted, finds its greatest expression in areas outside the city. The further away one sits from one’s neighbors, the greater the need (and desire) for self-reliance. That’s why suburbanites would rather mow their own lawns, despite the cost and inconvenience, than have to rely on the local council to do it for them, at the cost of higher taxes, even though the per-household tax amount would likely be less than the cost of doing the job oneself. It’s not just that the householders would do a better job than council workers — they would — but that they don’t want outsiders messing with their personal property.

(The converse of the above situation, incidentally, is residential trash collection — whereby a tax-funded council trash service is better than relying on individuals to perform that yucky job themselves, because human nature being what it is, people tend to procrastinate on yucky jobs.)

Individualism, because of that very self-reliance, also must perforce rely more on customs, manners and mores than the law. It’s far easier to do what’s expected than to rely on enforcement of behavior by an authority.

Individualism, incidentally, is not without its darker side. Lynching, for example, is where the “temporary group action” goes awry. But it should also be noted that even the extreme examples are not worthy of gross action to eliminate them. It’s not worth repealing the First Amendment right of freedom of association, for example, simply to attempt to end the practice of lynching: severe punishment of the lynching party for their actions will suffice, both to end the activities of those individuals, and to discourage further similar actions by others.

It should be noted, incidentally, that the ultimate form of individualist government lies not within libertarianism, as some might think. This is because libertarianism not only ignores the reality of the need for some form of constant collective action (e. national defense), but also because it over-exalts the concept of individualism — and ignores a few basic tenets of human nature in so doing.

The best form of government, for individualists, is one which will allow for the maximum amount of individualism — but which acknowledges the need for occasional yet constant management of the lapses in human nature (eg. a small police force), yet which devolves as much political power downwards, towards an ever-decreasing group size and ultimately, towards the individual.

It will come as no surprise, therefore, that the optimal form of government for this scenario is that of a representative republic — one in which all citizens may participate, and which, as much as possible, strives not to use its power on those citizens unless absolutely necessary, and then only to the degree to which the citizens themselves permit it to.

So much for individualism. What about the collectivists?

At the heart of collectivism lie one simple belief: that the problems of society are so vast and so deep, and the human character so flawed, that there needs be a “greater” agency to maintain order, and to “guide” that deeply-flawed human nature.

This is why there is a constant effort on the part of collectivists to “decide what’s best” for the individual, whether in the public or private domain, because of course under this philosophy, human beings are simply unable to make the “proper” decisions for themselves and for society as a whole.

The nature of collectivism plays on the herd instinct of human nature — of the “two heads are better than one” or of the “safety in numbers” mindsets, as well as the need for security which collective thought and action may supply.

Thus, for the collectivists, wisdom and security are best (and in extreme cases, only) derived from the group, and not from any individual.

So “it takes a village to raise a child”, for example, is one of the nods made towards collective wisdom, and indeed finds its roots in one of the oldest forms of collectivism, the tribal structure, or the “extended family”.

It’s why homeschoolers, for another example, are anathema to the collectivists, because the individuals (father and mother) who might dare to educate the child do not have the collective wisdom of the group designated as “educators”.

Security is likewise an activity that should not be undertaken by the individual — which is why the term “vigilante” (a subset of “lynch mob”) is most often used by collectivists to describe someone who acts in their own defense, and why individuals are compelled to rely on “the authorities” for their own protection.

Moreover, it helps if the populace is made more insecure by an apparent climate of lawlessness or insecurity — against which the best response is collective rather than individual action.

Just as individualism seems to flourish most in the country, or even in the outer suburban areas, it’s no surprise that collectivism flourishes most in urban areas — where there is collective housing, where private property is tiny in size, and where it’s easy to fall prey to gangs of predators (which form more easily because of the close proximity of other predators).

Finally, the feeling of insecurity is cemented by the constant feeling of helplessness — of being confronted by forces much larger than the individual. Hence the bogeymen of “capitalists, landlords, and militarists” (as described by James Cannon above) or “the rich” (as espoused by Democrats) and the constant reinforcement of “us vs. them” are all tools used by the collectivists to maintain their “class warfare”.

In truth, of course, the old European version of “class warfare” (where the upper classes were strongly entrenched by legal and self-perpetuating institutions such as the nobility and royalty, against which the poorer classes were indeed powerless) are about as relevant in today’s mercantilist society as the stagecoach is to a Greyhound bus.

Which is why our modern-day collectivists constantly rail against “the elites” (which are almost always synonymous with “the wealthy”) — even though wealth, in today’s America, is not only available in greater quantity and with more facility than in any society in the history of mankind.

It must really grate on these collectivists when their mantras become exposed for the rank fraud that they are — for instance, when it was discovered that in Sweden (for so long the collectivists’ “ideal” society), the average household has a lower standard of living than that of the average Black household in the U.S.A. (It should be noted that these findings came from a study done not by some capitalist think tank, but by a Swedish government department.)

Another piece of collectivist nonsense which is being rapidly debunked is in the area of crime — where the more the State authority assumes responsibility for the public safety, the greater the lawlessness. It’s not even that where there are more people, there is more crime: it’s that where people are denied the right to defend themselves, the crime rate is exponentially higher than elsewhere (on my “Red/Blue America” map, you can see that the “Gore counties” had a murder rate that was over five times higher than “Bush counties”, for example).

Finally, it should be noted that collectivism flourishes best in a society bereft of cultural institutions; where ancient and proven institutions such as the family or manners are reduced, redefined or marginalized so that they can be replaced by malleable governmental institutions and legal maxims (which can always be implemented by activist judges, or, if not pleasing to the collectivists, bypassed by loopholes).

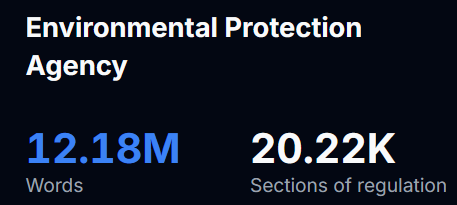

It helps too if no other group can become as powerful as the State apparatchiks — which, in capitalist America, means “the wealthy” are natural targets, and can be reduced back to the helpless proletariat by devices such as onerous taxation and/or hurdles towards the acquisition of further wealth. It helps immensely if all wealth is redefined as the property of the State rather than of any individual, of course.

For the collectivists, “the group” (ie. the majority) will always take precedence over the individual, and the State over smaller groups. Thus, of course, a representative republic, which devolves power downwards, is an anathema to the collectivists. Far better, of course, to replace the Electoral College with a “true democracy” (ie. popular vote) where areas with high population densities, and therefore their philosophies, would always hold sway over those rubes, those vigilantes, those gun nuts, those homeschoolers, those religious fundamentalists, those stupid inhabitants of “Flyover Country”.

There are many more examples of all this, but I think the above should have made the point.

This may also sound like a body slam directed towards the Democrat Party and their anointed would-be leaders, and it is — but it should also be noted that the Republicans are not immune to the collectivist impulse, either. Where the Republican Party suffers its most grievous loss of support is when they support — or do not actively oppose — collectivist goals (greater government involvement, gun control, higher taxes, and so on) instead of individualist goals.

I have read many people decry the “chasm” which separates us as a people. What I hope I’ve proved in this piece is that the chasm exists because of an irreconcilable conflict between two visions of what America should be: a collectivist nation on the European model (or even, a vassal state of a yet-greater, supranational institution such as the United Nations); or a representative republic based upon the Constitution as devised by the Founding Fathers.

Do not believe the propaganda. There is no compromise, no middle ground, and there is no “Third Way”.

It really is that simple.

Another one found in the archives, which I once thought I’d lost.