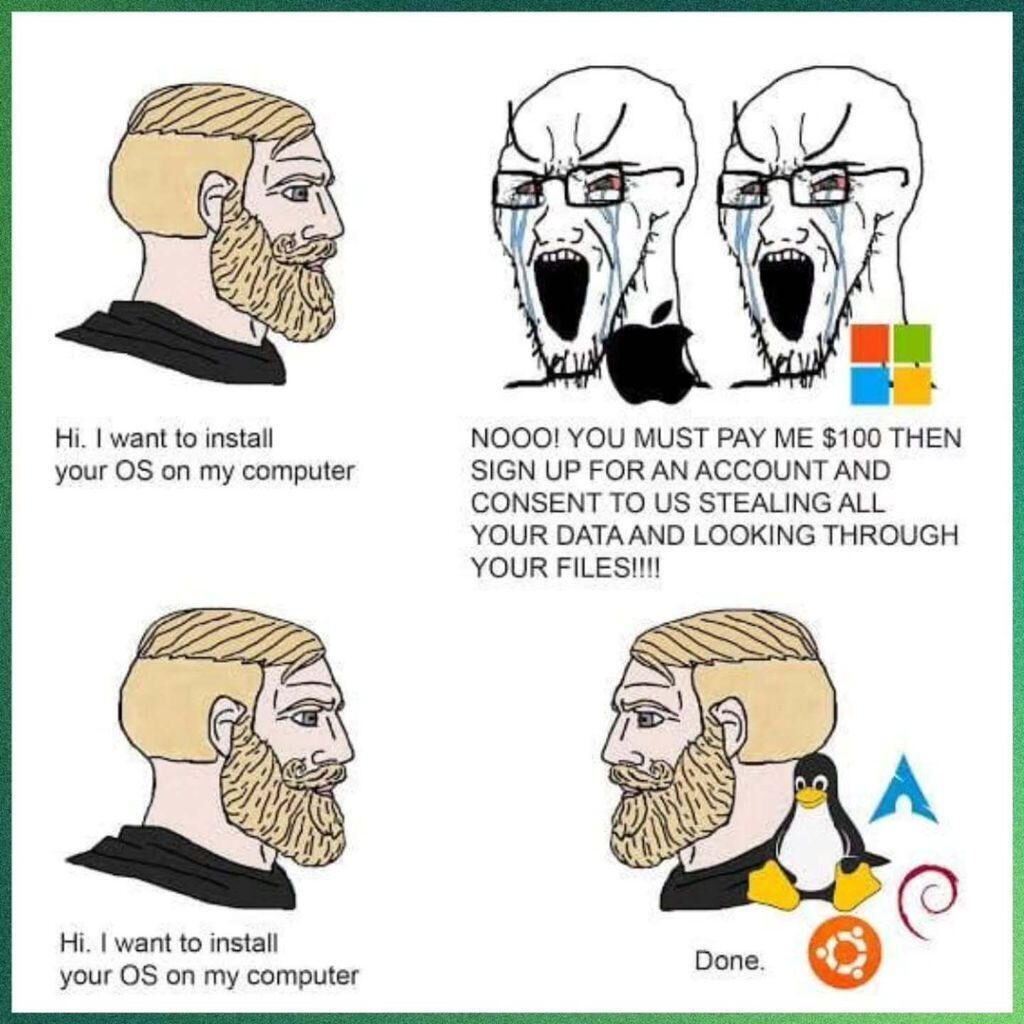

As someone who is actively looking to do this, can someone please explain the last panel to me?

…because I don’t understand the iconography. What are the products?

#StupidOldFart #OutOfTouch

As someone who is actively looking to do this, can someone please explain the last panel to me?

…because I don’t understand the iconography. What are the products?

#StupidOldFart #OutOfTouch

Over here, a couple of guys gripe about ten most irritating things about modern cars. To save you time, I’ve listed them here, with my thoughts:

Now go and watch the video — especially the last couple of minutes — because those guys are funny where I’m just fucking enraged.

Being a history buff, I’m always attracted to those Eeewww Choob videos that talk about the events that shaped our world. But now I look askance at these videos, and in most cases I turn them off after only a few minutes.

The reason? A.I. narration.

WTF is going on? How difficult can it be to hire a speaker — an actual human — to read a frigging script, instead of turning the script over to some machine to create a sorta-human voice?

I am, as my Readers will know, something of a stickler for correct speech, be it grammar or spelling (in print, of course), and that sticklishness extends very much, oh very much indeed to the spoken word as well.

When I hear mispronounced words — sometimes with several different pronounciations of the same word during the course of the narration — it irks me as much as would a series of different misspellings of the same word in print in the course of a single article or essay.

So no, I’ve made a decision to ignore any video, no matter how interesting the topic, if it uses that stupid, wooden A.I. nonsense.

I’m irritated almost as much, by the way, by A.I.-generated “photos” or pictures, but when it comes to history, of course, there’s not always a photographic record of the event or of the people involved, so I can sort of deal with it. Historical re-enaction using actual human beings can be horribly expensive, for not much benefit, so I can get along with phony actors and scenery.

But when it comes to speech? Ugh, no. There’s just too much dissonance — I mean, my own dissonance — for me to have any respect for the material, no matter the initial interest.

There it is: no more A.I. narration for me. I’d rather just buy a book on the topic.

I’ve been ranting about this issue for about as long as the nonsense first appeared with software-dependent cars. Now it seems as though it’s for real:

Hundreds of Russian Porsche owners have found their cars immobilized across the country, amid fears of deliberate satellite interference.

Drivers have complained that their vehicles have suddenly locked up, lost power and refused to start, as owners and dealerships warn of a growing wave of failures that has left hundreds of vehicles stuck in place.

The nationwide meltdown hit Porsche models built since 2013, which are all fitted with the brand’s factory vehicle tracking system (VTS) satellite-security unit.

The vehicles have been ‘bricked’ with their engines immobilized, due to connections with the satellite system being lost.

Okay: leaving aside the paranoia concerns — it’s the Daily Mail, of course there was going to be some panic warning — let’s just go with the system failure (regardless of cause) that causes one’s normally-reliable car to quit working.

I know I’m not the only person in the world who regards this “development” as creepy and worrisome. The fact that some situation could occur that renders one’s possession useless makes me deeply apprehensive.

As I said earlier, whether the immobilization was a factor of technology fail or else of some malignant third party is unimportant.

Note that this VTS thing is touted as a “security” feature — i.e. one that lessens the effect of the car being tampered with or stolen, a dubious benefit at best — and this supposed security guards against another feature (keyless or remote start) that seems to be all the rage among today’s cars, for no real reason that I can ascertain. In other words, car manufacturers have made it easier to steal their cars, and then have to come up with yet another feature that can negate that situation.

While some drivers were told to try a simple workaround by disconnecting their car batteries for at least 10 hours, others were advised to disable or reboot the Vehicle Tracking System, known as the VTS, which is linked to the alarm module.

Some owners have been stranded for days waiting for on-site diagnostics, tow trucks or emergency technicians.

There are reports of Russians resorting to ‘home-brew’ fixes – ripping out connectors, disconnecting batteries overnight, even dismantling the alarm module.

A few cars were revived after 10 hours without power, but others remained immobilized.

And they call this “improvement”?

By the way, it’s not just Porsche, of course.

Last year, MPs in the United Kingdom were warned that Beijing could remotely stop electric cars manufactured in China, as relations between the two nations deteriorated.

The previous year, lawmakers cautioned that tracking devices from China had been found in UK government vehicles.

Yeah duh, because China is asshoe.

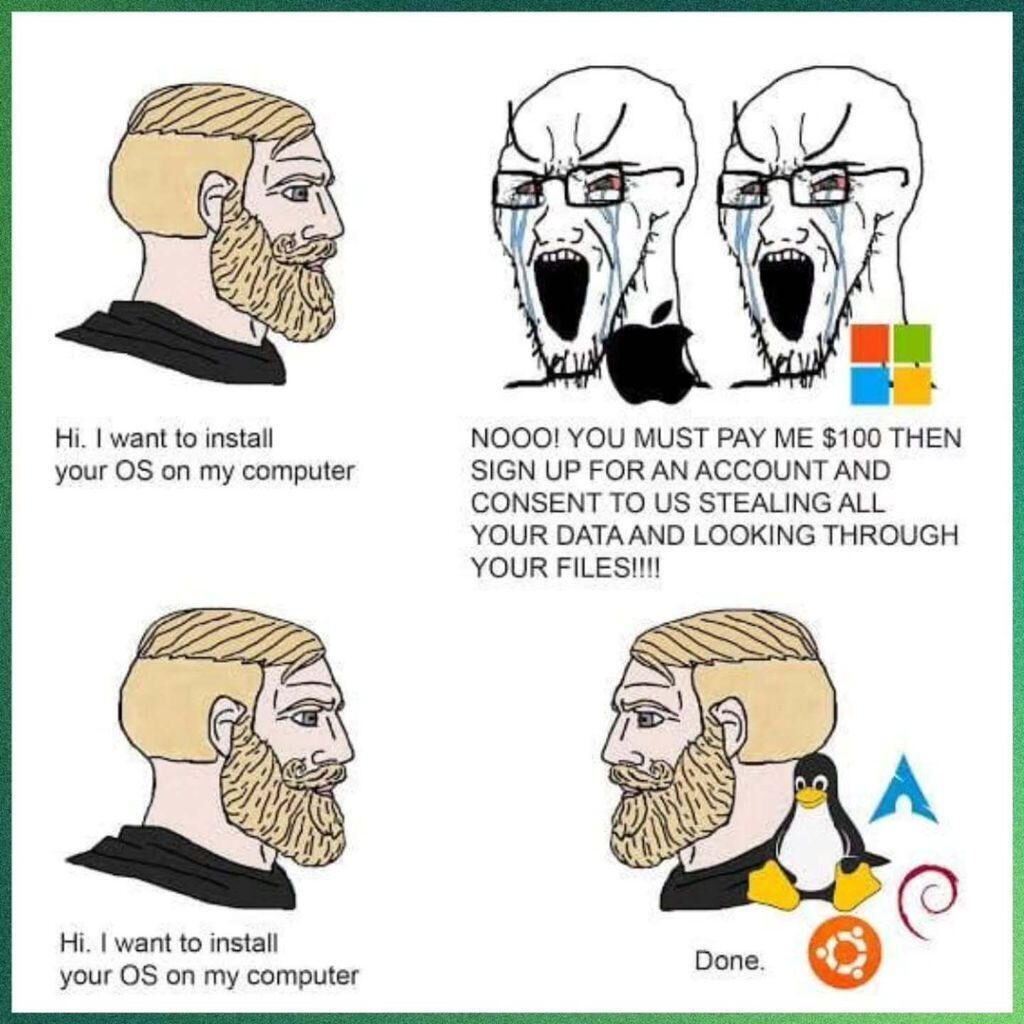

As for Porsche, this makes me realize why their older, non-VTS-equipped models are fetching premium prices in the second-hand market. I mean:

300 grand for an ’87 911? Are you kidding me? (Yeah, I know it’s been fully restored at a cost of about $50 grand — but even taking twice that amount off the asking price would still leave you with a $200 grand ask, which is ridiculous. No wonder the vintage sports car market is starting to tank.)

But at least this 911 isn’t going to stop working every time there’s a meteor shower, or whenever some controlling remote entity decides that you’ve been driving it too fast or too much.

It’s a fucking nightmare. And we’ve allowed it to happen.

…to the above QOTD: I wonder whether this irritation towards the modern world’s increasing (and likely over-) complexity is just a generational thing?

I have no idea as to the age of the commenter in this case, but I know that this disenchantment and hankering after a simpler life seems fairly common among people of my age, for the simple reason that it’s a common factor of life among my friends and, lest we forget, Readers of this here website.

But do the various “Gen” types feel the same way? I mean, we Olde Pharttes can remember (a bit) how much earlier times were less complicated and simpler. But in the case of Teh Youngins, are they even aware that life can be simpler, given that all they’ve ever experienced is Smartphones, the Internet, self-drive cars and refrigerators that can tell you when you’re running low on milk?

And considering that most Millennials, let alone the Gen X/Y/Z tribe don’t know how to change a flat tire, cook a meal from scratch and drive a stick shift, would they embrace a simpler world when so much of their daily life is smoothed by technology?

I suspect not, for the same reason that people of my generation would have no idea how to drive a horse-drawn carriage or be able to transmit a telegraph message in Morse code.

So our final few years of life on this planet seem doomed to be techno-centric instead of simple. What joy awaits us.

This report supports something I’ve been talking about for a while:

Major AI chatbots like ChatGPT struggle to distinguish between belief and fact, fueling concerns about their propensity to spread misinformation, per a dystopian paper in the journal Nature Machine Intelligence.

“Most models lack a robust understanding of the factive nature of knowledge — that knowledge inherently requires truth,” read the study, which was conducted by researchers at Stanford University.

They found this has worrying ramifications given the tech’s increased omnipresence in sectors from law to medicine, where the ability to differentiate “fact from fiction, becomes imperative,” per the paper.

“Failure to make such distinctions can mislead diagnoses, distort judicial judgments and amplify misinformation,” the researchers noted.

From a philosophical perspective, I have been extremely skeptical about A.I. from the very beginning. To me, the basic premise of the whole thing has a shaky premise: that what’s been written — and collated — online can form the basis for informed decisionmaking, and the stupid rush by corporations to adopt anything and everything A.I. (e.g. to lower salary costs by replacing humans with A.I.) threatens to undermine both our economic and social structures.

I have no real problem with A.I. being used for fluffy activities — PR releases and “academic” literary studies being examples, and more fool the users thereof — but I view with extreme concern the use of said “intelligence” to form real-life applications, particularly when the outcomes can be exceedingly harmful (and the examples of law and medicine quoted above are but two areas of great concern). Everyone should be worried about this, but it seems that few are — because A.I. is being seen as the Next Big Thing, like the Internet was regarded during the 1990s.

Anyone remember how that turned out?

Which leads me to the next caveat: the huge growth of investment in A.I. is exactly the same as the dotcom bubble of the 1990s. Then, nobody seemed to care about such mundane issues as “return on investment” because all the Smart Money seemed to think that there was profit in them thar hills somewhere, we just didn’t know where.

Sound familiar in the A.I. context?

Here’s where things get interesting. In the mid-to-late 1990s, I was managing my own IRA account, and my ROI was astounding: from memory, it was something like 35% per annum for about six or seven years (admittedly, off an extremely small startup base; we’re talking single-figure thousands here). But towards the end of the 1990s, I started to feel a sense of unease about the whole thing, and in mid-1999, I pulled out of every tech stock and went to cash.

The bubble popped in early 2000. When I analyzed the potential effect on my stock portfolio, I would have lost almost everything I’d invested in tech stocks, and only been kept afloat by a few investments in retail companies — small regional banks and pharmacy chains. I was saved only by that feeling of unease, that nagging feeling that the dotcom thing was getting too good to be true.

Even though I have no investment in A.I. today — for the most obvious of reasons, i.e. poverty — and I’m looking at the thing as a spectator rather than as a participant, I’m starting to get that same feeling in my gut as I did in 1999.

And I’m not the only one.

Michael Burry, who famously shorted the US housing market before its collapse in 2008, has bet over $1 billion that the share prices of AI chipmaker Nvidia and software company Palantir will fall — making a similar play, in other words, on the prediction that the AI industry will collapse.

According to the Securities and Exchange Commission filings, his fund, Scion Asset Management, bought $187.6 million in puts on Nvidia and $912 million in puts on Palantir.

Burry similarly made a long-term $1 billion bet from 2005 onwards against the US mortgage market, anticipating its collapse. His fund rose a whopping 489 percent when the market did subsequently fall apart in 2008.

It’s a major vote of no confidence in the AI industry, highlighting growing concerns that the sector is growing into an enormous bubble that could take the US economy with it if it were to lead to a crash.

In the late 2000s, by the way, anyone with a brain could see that the housing bubble, based on indiscriminate loans to unqualified buyers, was doomed to end bad badly; yet people continued to think that the growth in the housing market was both infinite and sound (in today’s parlance, that overused word “sustainable”). Of course it wasn’t, and guys like Burry made, as noted above, billions upon its collapse.

I see no essential difference between the dotcom, real estate and A.I. bubbles.

The difference between the first two and the third, however, is the gigantic financial upfront investment that A.I. requires in electrical supply in order for the thing to work properly, or even at all. That capacity just isn’t there, hence the scramble for companies like Microsoft to create the capacity by, for example, investing in nuclear power generation facilities — at no small cost — in order to feed A.I.’s seemingly insatiable demand for processing power.

This is not going to end well.

But from my perspective, that’s not a bad thing because at the heart of the matter, I think that A.I. is a bridge too far in the human condition — and believe me, despite all my grumblings about the unseemly growth of technology in running our day-to-day lives, I’m no Luddite.

I just try to keep a healthy distinction between fact and fantasy.