Chapter Four: How A Band Works

In case it hasn’t been clear in this narrative so far: I had a dream and an ambition, but not a single clue how to make that happen. To call me “clueless” would imply that I had even the faintest idea of where I could find a clue, or any inkling of a clue’s existence.

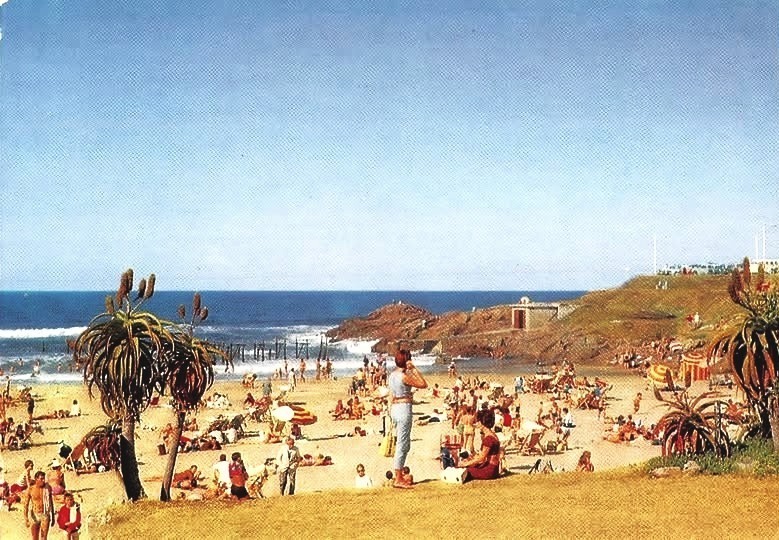

But when I discovered Shalima, the Palm Grove’s resident band that year, I started to get the picture.

Let me first, however, list the dramatis personae who comprised Shalima, because almost all of them would be important to me (pics courtesy of Max):

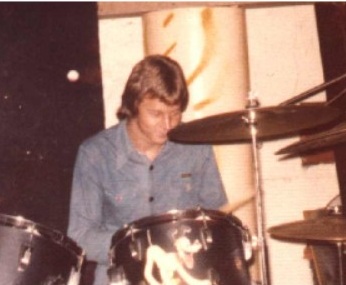

Pete The Drummer

A rock-solid drummer who kept perfect tempo, and put down a lovely beat.

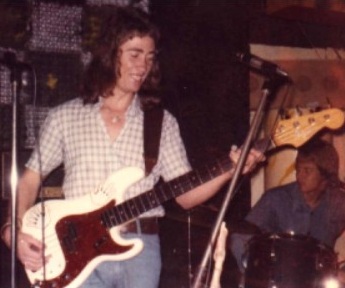

Richard The Bassist

Richard was a wonderful bass player. Good grief, looking at the ease with which he played his Fender Jazz Precision bass, sometimes so inebriated that he could barely stand (to be explained later), I nearly quit on the spot.

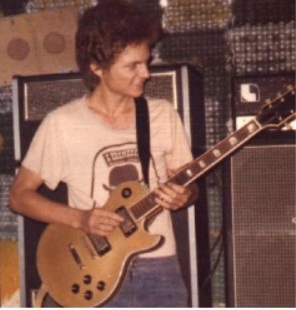

Jeff The Lead Guitarist

Jeff was just as good on lead guitar. It seemed like there was no guitar part he couldn’t play, note-perfect. If he had a fault, Jeff was shy and self-effacing, so much so that I think he would occasionally hold back a little with his lead solos – but when he did cut loose, it was an awesome experience.

Tommy Sean The Vocalist

Tommy Sean (whose surname I include because it’ll be important later) had a powerful and very distinctive voice, but which he seemed to lose as the evening went on. Clearly, he hadn’t been vocally trained at all, because he’d wear his voice out fairly quickly. The immense quantities of beer he’d consume during the evening couldn’t have helped much, either.

Rory (“Max”) on keyboards

Finally, there was Max. If ever I’m asked, as I have often been, who most influenced my musical career, it would be Max — not so much for his considerable musical ability, but through the way he managed the band and the different personalities to keep them on track. Max had started out as Shalima’s bass player, but when Richard arrived on the scene he moved to keyboards.

Sheila (the pregnant book-reader, and Max’s wife) featured occasionally on keyboards and vocals.

Now, their music; and man, this bunch of Rhodesians could play. Of course, as with all club bands in South Africa at the time, their repertoire consisted of covers of hit records, and only hit records. They didn’t play any of their own stuff (if indeed they had any), but what struck me the most was that every song sounded precisely like the original artist’s recording, with only the occasional variance being of course the vocal sound.

Incidentally, one of the first songs I heard them play was the 3 Degrees hit When Will I see You Again? and the (very) pregnant Sheila had a voice of lovely clarity, absolutely the equivalent of the song’s original lead singer. That was impressive by itself; but what stunned me was that Shalima’s backing harmony vocals mimicked the soprano voices of the 3 Degrees perfectly.

I told you earlier that I had no idea, and in this case I had no idea that male singers could sing female voices, in a rock context. Of course I knew about falsetto – I could sing pretty much any female vocal part myself that way – but I’d never known it could be used in performance, and especially in rock music. Like I said: no clue.

Anyway, the band played the first set, each song impressing me more than the previous one, and then they took a break, going over to sit at a table clearly reserved for their use on the side of the dance floor. And then they each proceeded to drink three beers during the next fifteen minutes.

Back on stage, they continued on with the performance, and more drinks during the breaks, and so on.

I wanted to talk to them, but I felt somewhat intimidated because, let’s be honest, I wasn’t musician enough to walk on stage with them let alone play what they did. Finally, though, as the evening started to wind down at about midnight and I’d had a couple beers myself, I plucked up some courage and walked over to Richard, having prepared a question about his amp and guitar as a conversation-starter.

He was polite but a little diffident, but when he asked me what had brought me to Margate and I told him, his attitude changed completely. “You’re in Mike du Preez’s band up in the hotel? Wow!” Clearly, I wasn’t just some fan-boy or drunkard off the street; I was a musician. “Come and meet the rest of the guys,” he said, and pulled me over to the band’s table.

And thus started a relationship which was to last years, and which helped me get into professional rock music more than just about anything else.

I learned so much just from watching these guys. From a playing perspective, they were consummate professionals: never late to get on stage, always playing the music most guaranteed to fill the dance floor, no messing around between songs, in fact they had none of the bad habits that bedevil “garage bands”, and I was extremely impressed.

Also, Max was the band’s leader and driving force: no arguments on stage, no nonsense of any kind: his decisions were policy, and the band had to fit in. As a keyboards player, he was more than competent, but considering that keyboards were essentially his second instrument, it should be known that he never held the band back, musically speaking. (That’s not always the case, by the way, as you will see later in this narrative.) Unsurprisingly, he ended up being a piano teacher many years later.

Over the next few weeks, I learned from these guys how to play in a band — and more importantly, how a band worked: not just the playing, but the management and attitudes.

In the first place, I was only nineteen, but all the others were in their thirties (except Jeff, who was a little younger), and they’d already been playing either professionally or semi-pro for over a decade. I had no idea that one could do this. I mean, I knew about other famous South African bands who’d been around for a while (the Staccatos, the Rising Sons, the Blue Jeans, Four Jacks and a Jill… the list was long); but while they’d been around for years, they’d all had top 10 records on the South African hit parade, which to me justified their longevity. Yet here was Shalima, of whom I knew nothing, and they’d been playing music as a full-time job in club after club, year after year.

You could have a career in rock music without having a record contract or hit record.

This made all the difference to me, because I’d always thought that a career in rock music required a hit record — and I also knew that the number of hit records (and the bands that played them) were only the top 2% of the bands. (As with all things, whether sports, music or any activity, only a very few end up being truly successful.)

So one didn’t have to be a rock star to make a living. You only had to be as good as, well, Shalima. And all you had to do was get good enough to play on the club circuit. Once again, as a teenager I’d been woefully ignorant of the club scene — thank you, boarding school — but listening to the Shalima guys talk, I realized that there were lots of opportunities around, far more than I’d ever imagined.

Then, a brief splash of cold water.

I mentioned to the others in the Trio how much I liked Shalima, how impressed I was with their musicianship, why I’d never heard of them before, and why they hadn’t played in Johannesburg. Dick the dick scoffed. “They’re what I’d call a good gig band,” he said. “Maybe high school dances, weddings, that kind of thing. But in a Joburg club? No way.” And to my amazement, Mike du Preez nodded in agreement.

I didn’t believe them. So the next time I was down in the Grove, I asked Max why they hadn’t played in Johannesburg. “We’re not good enough to play Joburg,” he said bluntly.

Bloody hell. Clearly, there was more work to be done if I was going to make a go of being a pro.

At this point, some two weeks after I’d started playing in the Trio, I started to get better on the bass. No longer did I have to play “find the note” or search my memory for what song it was; it all started to become a little easier, I stopped approaching each night with something akin to dread, and I actually started to enjoy myself. Paradoxically, as I relaxed the whole thing came more easily.

But that “not good enough to play in Johannesburg” warning had stuck; so I started to practice, really practice on the old Hofner Beatle bass. One day I decided to teach myself how to play what’s known as a “walking” bass line, whereby the notes are played four to a bar, but “walking” up and down the scale. (Ah, so this was why we had to practice scales: now it all made sense.) It took me more than a few days, because of course you have to learn the scales for each of the keys in the key signature (A, A-flat, A-sharp, B, B-flat etc. all the way up to G. And then of course the minor keys thereof.) But I stuck to it, concentrating especially on the more common keys the Trio was playing, and eventually I could play the runs with some confidence. Then I taught myself the classic rock ‘n roll bass riffs — the Chuck Berry / Albert King / Bo Diddley standards — and with my newfound fluency, they came quite easily.

Then, kismet. One of the songs the Trio played was the old Art Blakey song Moanin’. (I invite y’all to listen to it now, as background for this part of the story.) I’d struggled mightily with this one in the beginning, because Jazz. But once I figured out the scales and walking thing, it became relatively easy to play. So one night I asked Mike, ever so casually, “How about Moanin’?” He nodded, and played the opening riff — then stared at me open-mouthed as I walked my way around the complex melody. Even Dick was impressed when I managed to scratch out a rudimentary bass solo — the first I’d ever played. For the first time since we’d opened, the Trio really hit a groove.

Unfortunately, this meant that Mike started to play ever-more difficult jazz standards, but to my amazement they weren’t all that difficult. I’d figured it out. That’s not to say I was any good at it, of course; but I was well on the way to becoming somewhat competent.

Musical interlude: One day I was sitting by myself at a cafe somewhere in “downtown” Margate (there was one main drag) drinking a cup of coffee when I happened to glance out the window and saw a familiar car being parked right next to the cafe. I knew the car, a Mini, because it belonged to my old schoolfriend and GROBS bandmate Gibby. So of course I raced outside, grabbed him and pulled him in for a cuppa. His family owned a seaside cottage in a little town south of Margate, and he had come up to do some grocery shopping, I think. Anyway, we spent the rest of the day together, and then I remembered that Sunday night at the Grove featured “talent” competitions — dancing on Sundays being streng verboten in ultra-Christian South Africa back then — and so I dragged Andy off to participate. I don’t think either of us cared about the competition, though: it was just a chance to play on stage together.

Anyway, I introduced him to the Shalima guys, but Max didn’t want to let us enter the competition — “Kim, you’re a pro and pros aren’t allowed” — but I prevailed upon him by saying that I didn’t want to compete; I just wanted to back Gibby and play on stage with him. So Max relented, and we played, I think, Santana’s Evil Ways with Gibby improvising the whole thing on Max’s Hammond organ, and doing an excellent job of it, too.

As it happened, he didn’t win the competition; it was won by a tiny, pint-sized girl named Ingrid (“Ingi”) who played a thunderous, virtuoso number on Pete’s drum kit, accompanied by the other Shalima guys. (We’ll hear more of Ingi later.)

Then one Saturday afternoon the Trio was playing an “extra” set in the dining room — I think it was a wedding reception, booked earlier in the year — when the good stuff happened.

The Shalima guys had never heard the Trio play because our bands’ set times always coincided. On this occasion, however, they had the afternoon off, they heard the music coming from the dining room and set out to investigate.

I’ve mentioned that our “stage” was really just an area between the small dance floor and kitchen entrance, separated from the latter by an indoor lattice covered with plastic ivy. So it was behind this screen where Max, Tommy Sean and Richard hid, to listen to us play.

As it happened, Mike had just dropped a piece of sheet music in front of me and asked, ever so casually, “Think you can busk your way through this?” (If memory serves, I think it was a pared-down version of Deep Purple.) So seeing that it was a really slow ballad, I just nodded and made sure that I had the key established and off we went. About halfway through the song I became aware of some half-whispered comments coming from behind the screen, and realized that the Shalima guys were there. Of course, this made me sweat, but somehow I made it through the piece.

Then Mike winked at me, and launched into the intro to Moanin’. (He has a special place in my heart for that little act of kindness.)

As it happened, that was the last song of the set, so I put the bass down and went to chat to my friends. The first to speak was Tommy.

“You can read music?” I nodded. Then came Richard.

“Kim, you’re a fucking lying liar.”

“Why?”

“You told us you couldn’t play the bass, you asshole.”

“Eh, you caught me on a good night.”

Then Max: “Was that the first time you’d ever played that slow song?”

“Yup. Mike likes to throw different stuff at me sometimes.”

“Cool.”

So my meager stock rose, at least with the guys I wanted to impress, and along with it, some small degree of self-esteem. I was still very conscious of my shortcomings, even though I’d come quite a long way in the past weeks.

I’d settled into the life of a professional musician very easily, especially so in the company of the Shalima guys. During the day we had nothing to do, so we screwed around, constantly: darts matches in pubs, putt-putt competitions, girls, and always, beer in monumental quantities. This was how we spent our lives together in Margate. As the wedding reception had been a “side gig”, the Trio had been paid separately from our hotel gig, and to my astonishment I ended up with about 200 Rands as my share. This was more money at one time than I’d seen in the past two years, so of course I blew it all on the aforesaid beer with the guys, not to mention ill-advised bets on the darts matches (Tommy was an absolute wizard, I discovered to my chagrin, and I only managed to get a little back playing putt-putt because I was if not the best, then at least close to being the best player of all of us).

Then one night, after the Trio and Shalima had finished for the night, Max and I went out for a drive in my Fiat, just to chat away about this and that. Then at about 3am I asked him, “Do you want to listen to some new music?” His response was immediate. “Of course I want to listen to new music. This is my job.” (Lesson learned: if you’re going to be a pro, you have to immerse yourself in music and treat it as part of your job.)

I played him a tape of Bad Company’s first album. Max listened to it without comment, then said, “Play that first song again.” Then: “Can I borrow this tape?”

The next night I went down to the Grove, and at the end of the song they were playing, Max said over the PA, “This next one’s for Kim,” and Shalima launched into a note-perfect cover of Can’t Get Enough. They’d learned it already. (Another lesson learned: you’ve gotta stay current, and be good enough to learn a new song quickly.)

One side note: just before Christmas, the Trio had a very brief hiatus. Dick the dick went back up to Johannesburg to get married (!), and returned the very next day with his new bride, a pleasant, mid-forties auburn-haired woman named Moira, and his freshly-high-school-graduated daughter. I took to Moira immediately — I had no idea what she saw in Dick — and as all four of us were now sharing that tiny cottage, I also took the opportunity to deflower his daughter one afternoon, because Musicians Are Scum. (Moira will feature briefly later on, hence my mention of her here.) Fortunately, I was able to keep away from the now-besotted daughter because the Trio was really busy, and when not playing I was always racing off to hang out with Shalima.

About two nights before the gig was coming to an end, I walked into the restaurant to find a stranger sitting with Mike and Dick. “Hey, Kim, this is Barry,” was the casual intro, “He’s a bassist I know from Johannesburg.”

So I invited him to play a couple songs with the Trio, because that’s the gentlemanly thing to do, of course; and Barry proceeded to play that old Hofner like it had never been played before. Very humbling.

At the end of the evening, I was just getting ready to leave when I heard Dick whisper to his wife: “If Mike had known Barry was available before we came down, he’d have fired Kim on the turn. Hell, if we’d known he was available after the first couple of weeks we’d have replaced Kim anyway.”

Even more humbling. Clearly, there was a cold-blooded side to professional music too.

At that point, though, it wasn’t that important, because the New Year came and with it, the end of the gig, my first gig — professional, even — as a bass player. As I said my sad goodbyes to that ragged bunch of Rhodesians, I made them promise to look me up should they ever get a club gig in Johannesburg or Pretoria.

Somehow, I was going to have to get it together when I got back to Johannesburg, and I had no idea how I was going to do that.

– 0 –